Last week, David Corey, the Bertarelli Professor of Translational Medical Science at Harvard Medical School, and colleagues announced that they had identified a new viral vector for the delivery of genes to hair cells in the inner ear. Now, scientists in the US have published two papers that show that in preclinical tests improved gene therapy has restored hearing, to a much higher degree than before, and balance in genetically deaf mice.

The work, which was part-funded by the Bertarelli Foundation, follows on from the 2015 study that demonstrated the restoration of rudimentary hearing. The two new papers, which used a new vector to transfer the gene therapy, now report much improved hearing, down to 25 decibels, “the equivalent of a whisper.”

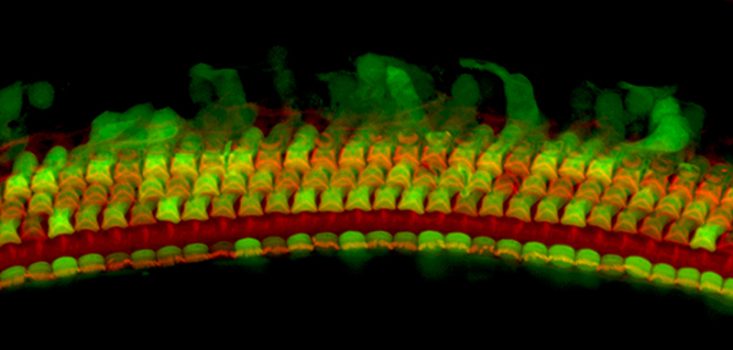

The first study, the senior investigators on which were Harvard’s Jeffrey Holt, Konstantina Stankovic and Luk Vandenberghe, showed that a new synthetic vector, Anc80, “safely transfers genes to the hard-to-reach outer hair cells”. Previously, vectors had only been able to penetrate the cochlea’s inner hair cells.

“We have shown that Anc80 works remarkably well in terms of infecting cells of interest in the inner ear. With more than 100 genes already known to cause deafness in humans, there are many patients who may eventually benefit from this technology.”

Konstantina Stankovic, Associate Professor of Otolaryngology at Harvard Medical School

The second paper used the new vector to deliver a “specific corrected gene in a mouse model of Usher syndrome, the most common genetic form of deaf-blindness that also impairs balance function.” The study, which was led by Harvard’s Gwenaëlle Géléoc, reported remarkable efficacy in restoring hearing to deaf mice that were treated soon after birth. The therapy also restored balance, “enabling the mice to stay on a rotating rod for longer periods without falling off.”

There is still a great deal of work to be done before the potential treatment can be bought to patients and the authors issued one caveat: Hearing was restored in mice that were treated straight from birth, but not in those when the therapy was delayed by 10 to 12 days. Further research will aim to determine the reasons for this, but as Jeffrey Holt, a co-author of the second paper, says, it is a “landmark study. Here we show, for the first time, that by delivering the correct gene sequence to a large number of sensory cells in the ear, we can restore both hearing and balance to near-normal levels.”

There is more in the news story on Harvard Medical School’s website, here.